A

lot of our readers don't have the budget to do two weeks of partying and working

in Jamaica. What lesson should they derive from Live doing that as part of the

songwriting stage of Secret Samadhi?

A

lot of our readers don't have the budget to do two weeks of partying and working

in Jamaica. What lesson should they derive from Live doing that as part of the

songwriting stage of Secret Samadhi?Musician

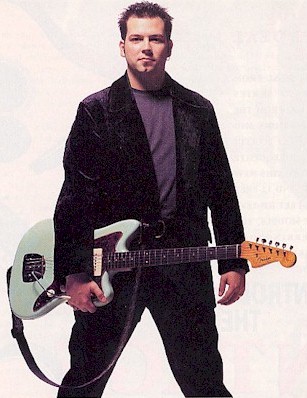

April 1997

Excerpts with Chad

Taylor from

Topping Copper: The Trials & Triumph of Live

by Robert L. Doerschuk

A

lot of our readers don't have the budget to do two weeks of partying and working

in Jamaica. What lesson should they derive from Live doing that as part of the

songwriting stage of Secret Samadhi?

A

lot of our readers don't have the budget to do two weeks of partying and working

in Jamaica. What lesson should they derive from Live doing that as part of the

songwriting stage of Secret Samadhi?

The most important lesson is that it's more important to be friends than musicians or songwriters. Being in a band should be about having fun. We could have done the same thing, had we not traveled to every city in the world and played our music there, if we had decided that every night at eight o'clock we'd meet at the corner bar and talk with each other. See, I think that's where drugs come into play with bands. If everybody's on the same drug, it gives you a common plateau. For Live it's always been more about open communication. Our long-term friendship, not what we're all doing individually, creates the common ground where we write. Our shared history enables us to write. So I would recommend to most bands that they start by learning how to get along with each other. If you pick an environment and start doing that, and if you don't develop anything in an hour or two, stop. Don't get down; just say, "Hey, man, that was fun. I'll meet you tomorrow night at eight." Eventually something will come.

That band consciousness you're talking about is integral to the whole concept of rock & roll.

What makes a rock & roll band different from anything else is that there has to be a spiritual connection. When you get that, it's the greatest of bands. With an average band, you can tell they want to make music together but they're not combining spiritually. With the Stones or the Beatles, there was a bond between the guys in those bands that h as not been duplicated since, maybe with the exception of R.E.M. or U2. Pearl Jam is one of those bands. I always wonder how hard it must be for those guys to stick together, to be a band and function as a songwriting unit, with all these outer elements - money, fame, success - influencing them. As close-knit as we are, I don't know if we could have made it though if success had come as fast to us as it did for those guys.

In some cases, the appropriate thing might be to split up the band. Some bands, like the Doors, make on magical statement, and then they might as well hand it up, given the corrosive effect the business obviously had on their later work.

But don't you think it was less about the Doors as a band and more about a group of songs they came up with at one time? Those thoughts were only gonna come out of Jim Morrison at one time.

But it's also the moment. I mean, how many times could they have played "The End" as they did on the album?

Certainly it can be about the moment, but overall it should be mainly about the song. Songs stand the test of time. What I'm looking for is integrity, for people who put their music and their band above all else in their lives. For example, look at the struggles that Oasis were going through. You just can't help but think to yourself, "Why are they ruining the dream? Why are they spoiling what's so precious?" You're only given so many opportunities in life. You have to seize them, not for success but because each of us is on a path, and if a path is pointing you in a particular direction, that's where you go.

During that long period before you played for any record companies, did you guys ever think about sending tapes to labels, or showcasing at South By Southwest? Or did you consciously decide not to try to break into business?

Well, you've got to understand that where we grew up no previous bands had done that, so we didn't know the process. We had no idea what steps to take to become successful. For me, defining those steps of what it was gonna take to become a great band started by choosing mentors and watching what they had done. I read a U2 book called Unforgettable Fire in the summer between my junior and senior years in high school, and I remember writing notes in the side margin: For example, "U2 got a manager"; I wrote down, "Get a manager." Literally, step-by-step, I outlined how to go from being a band that can play at the corner bar to a band that can play at the corner stadium. All I was doing was looking at what happened to other bands. We certainly didn't have anybody locally to attach ourselves to, so we did it with more national figures, whoever we could relate to. For example, I remember reading a passage about the Edge, and after four or five paragraphs I thought I was reading about myself. It was in that moment that I realized that I would be as my mentor. I would be the Paul McCartney or the John Lennon or the Bono or the Michael Stipe, whoever it was. We would have the chance to be successful, and we would be the best band in the world.

![]()

At that stage of your career, that sounds more like hallucination than a coherent strategy.

But that kind of belief is the most important thing you can have. You have to believe in yourself because if you don't, nobody else will. For as many people who supported us, there were ten times as many who thought we were terrible - and probably still think we're terrible. My teachers and my peers and my friends all through high school were all doubters. Once we graduated from high school, my employers, people I worked with eight hours a day, were doubters. That's the one factor that doesn't change, so it makes no sense to concentrate on it. Even today; there are as many bad reviews as good reviews, so you might as well convince yourself that you are the best band.

Aren't there different levels of doubt? It's one thing to say "You guys suck," but maybe some of your colleagues were saying, "Look at this rotten business of music. No matter how great you are, the odds are still against you."

Well, I think there's no such thing as a great band that doesn't success.

That depends on what you mean by success.

Exactly. Live was successful the day we decided not to go to college and to dedicate ourselves instead to the band. Whether we ever sold a record or wrote another song, that was the day we became successful. Up to that point in our lives, we had been content to go along in mainstream society. I think it was the biggest spiritual decision we ever made, to remove ourselves and go into that isolation I was talking about earlier. Live is not about the business of selling records or tickets to shows, it's about conveying a spiritual energy that we were lucky enough to bump into. That's a much bigger goal than just selling product.

Your decision to isolate yourselves also marked the point where you put your collective identity as a band above your individual concerns.

That is a rock & roll band. I keep telling my friends in younger bands to stop thinking about the record companies, stop thinking about the tour bus or the gear you want to buy. Start thinking about the fun you're going to have. Success, in music business terms, ruins a lot of great musicians. Being tru to what's inside your heart is what people and record companies gravitate toward. If you're honest. like Keith Richards about his drug habits and drinking, people appreciate that. I appreciate it. Thank God he lived that lifestyle for me, because I can say "Wow, that was great!" and not have to do it myself.

You're expressing a real faith that listeners, yourself included, will be able to discern honesty in a song. But some of the greatest writers out there were something less than honest in their presentations. Bruce Springsteen created a fictitious world centered around cruising in cars, though he didn't even drive during those years he so evocatively celebrated.

But when artists are honest to themselves, it always comes across. Bruce Springsteen's a great example. I can honestly say I didn't listen to him when I was growing up, until I read this Rolling Stone article where he talked about how he likes our band, our intensity and integrity. For him to realize that, does he not have integrity himself? So I bought some Bruce Springsteen records, some of which to this day I can't understand, but I tell you, when the guy is singing, he means what he's saying. I don't necessarily get it, but there is an integrity there that you can't discount.

Just before I finished speaking with Ed, he suggested I ask you to talk about "Lakini's Juice" because, he said, "in this song is the future of the band." Certainly done before, with the proliferation of diminished fifths.

When I was writing "Lakini's Juice" it was four or five o'clock in the morning. I had just polished off a bottle of cabernet, and I was drawing on the emotions I had gotten from seeing some movie earlier that night - I wish I could remember which one it was. But the song was like a call to arms, a war song. I remember that as I was writing it I envisioned a shotgun when you pump it and a shell pops out, like chu-choong, chu-choong, and then before I knew it the chords started coming together. I felt more free to experiment because I was really intoxicated; it had a lot to do with the fact that my hands wouldn't keep up with where my thoughts were going. The alcohol was actually hindering my ability to play guitar, which is pretty bad when you're already low on the scale. This was the first song I ever wrote in open tuning, and I did that so I could at least get one chord in there without having to keep my hand on the guitar.

Without

getting too technical, there were some interesting dissonances in

"Graze," especially where you play this major triad against a minor

chord in each chorus.

Without

getting too technical, there were some interesting dissonances in

"Graze," especially where you play this major triad against a minor

chord in each chorus.

It had totally to do with feeling. Because Ed's focus is on melody and lyrics, he tends to not want to pay attention to the guitar. He doesn't play like a traditional guitar player would, so it's a very delicate thing to balance with him. For example, he tends to do the strumming stuff, so I try to stay out of his way. If I can not play at all, I'm usually happy; I like being the guy who's just sort of making noise in the background. But when the song starts to take on heat, I get the ball from Ed, and I want to take the song in a different direction. In that song, the major over the minor just sounded right to me. I was just playing with the melody. Because Ed and I don't have a communication based on "What are you playing? What should I play?" Ed won't say, "I wrote this song, and it goes G-C-D." He'll play it and we'll fold into it. We don't relate to each other in musical terms. I mean, you could even ask me what key this song is in, and I wouldn't have a clue. I couldn't tell you what chords I'm playing. I don't have that relationship with my guitar at all.

You know where to put your hand on the neck, right?

Well, when I play with friends, they'll tell me what key the song is in, and I'll just work my way up the scale very quietly, without being obtrusive to the band, until I find two or three notes that seem to work. And those are the only two or three notes I'll play in the entire song. When it comes time for me to play, I'll put as much feeling into that first note as anybody would put into any chord.

But you don't associate that fret with, say, a C or a D?

Not at all. My background to music comes from playing trumpet.

Were you a better trumpeter than guitarist?

Oh, no way. I didn't have the purity. The notes, the actual written music, got in my way. My connection to the guitar is more intuitive. A friend of mine showed me some starter chords: E, B, C, and A minor. What the hell more do you need than that? I mean, come on! That's every song in the world, right? I have a great admiration for people who do know what they're playing. But my favorite guitar player, hands down, is Neil Young. He's the quintessential guy who just can't play. Occasionally he'll fumble around and get the right note and the right time, and he's just flaring on that whammy bar and banging the shit out of the instrument. Next thing you know, there's chills all over your body. He is so limited, but there's something beautiful about that kind of simplicity in rock & roll.

While you might not go out of your way to figure out which note is which, you do seem to put a lot of attention to nuances of tone throughout Secret Samadhi.

I'm really glad you picked up on the tonal thing. Hendrix and Neil Young are my two favorite guitarists, more because of their tones than their playing ability. Tone is the most essential part of the guitar. Different tones instantly evoke different emotions, no matter what the notes are. If you turn an amplifier up louder than it should ever go and you blast it with the lowest note you can possibly hit to make it fart, it evokes a different emotion than an amp with a pretty clean sound and a nice reverb. That started with classical music, the cannons in the 1812 Overture. Cannons don't particularly play notes, but they sure evoke tone. My guitar at times had to be the cannons in the 1812 Overture, but at times it also had to be the violins.

Why is it that none of the songs on Secret Samadhi fade out?

Because we wanted it to be real. Fading a song adds an element of "walking off in the distance," like at the end of a movie. That's fine and dandy in a movie, but on a record it's important to bring that realism in that is a four-piece rock & roll band, and most of what you listen to was recorded live, four of us playing in the studio. We really do end the songs. We really do drop our instruments and let the chords ring out too long. So now on every Live record I get one ending where I feed back reverb for eight minutes. It's in my contract [laughs]!